MAJORITY of our public servants and other officials are engrossed in official duties of state until retirement. They hardly will spare their precious time on issues clearly outside their official call to duty.

MAJORITY of our public servants and other officials are engrossed in official duties of state until retirement. They hardly will spare their precious time on issues clearly outside their official call to duty.

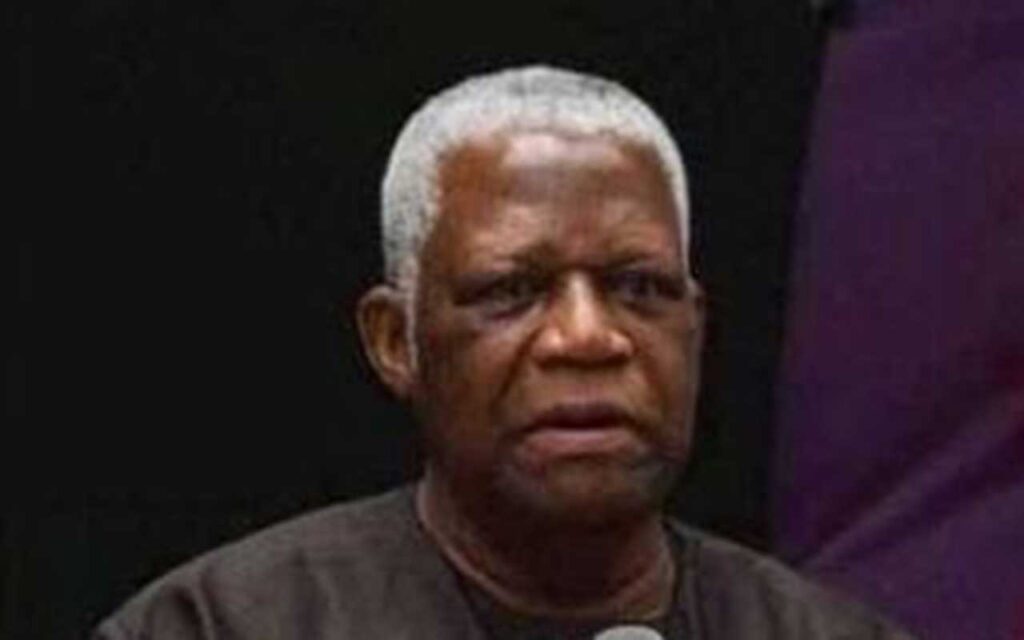

Thus the question: how does a highly placed and quintessential diplomat, accomplished civil servant, scholar and seasoned technocrat manage his crowded schedule to have the luxury of engaging in a demanding task of intellectual exercise such as documenting a master piece on a rather contentious topic of state formation in Africa? Ambassador Godknows Boladei Igali is an accomplished historian with a Latin American professional training background and in this profound 310-page work ‘Perspectives on Nation-State Formation in Contemporary Africa’ from the stable of Trafford Publishing, offered a critical historical survey and analysis of the intricate and complex processes associated with nation state formation and integration in Africa from the earliest period to the present era.

The evolution of the present structure of the global system may have started in 1648 when the treaty of Westphalia was signed. In the context of Africa, how did the state system evolve? The author in a revealing and free flowing prose made credible effort to present fresh insights and inspiring perspectives to the challenges of integration in Africa including the debilitating dilemma of state formation in the continent.

While in the 1990s, Latin American countries were already celebrating half a century of democratic stabilization, states in Africa were beginning to undertake the process of demilitarization in order to commence the search for democratic growth.

These countries in Africa were assailed by the same set of challenges notably ‘how to create institutions, processes, and attitudes that would foster national integration and see the emergence of new nation-states.’

Perspectives on Nation-State Formation in Contemporary Africa contains 14 well -crafted chapters, each addressing a fundamental issue of relevance to the continent. From the dilemma of multiple identities and loyalties through the political and organisational structures in ancient Africa, Africa’s relations with outsiders, colonial experience, and nationalism, decolonisation to the sociology of colonialism, nation-state formation and democratisation challenges all received appropriate attention in this volume.

This book will find enough space in the personal and institutional libraries of seekers of truth as it concerns Africa. Its assessment without sentiment of the African condition ranks same with similar efforts by Walter Rodney, Ali Mazrui and Bade Onimode amongst others.

For instance, the author’s ideas and how he espoused them in chapters three to five i.e Euro-African Relations: From Diplomacy to Servitude, Euro-African Relations: The Phase of Legitimate Trade and Gunboat Diplomacy and Colonial Administration, and Decolonization, 1900-1960 is refreshingly desirable to the point of remembering several epic works of the past.

While Rodney’s ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’ indicted Europe on African underdevelopment, Bade Onimode’s Africa in the World of the 21st Century did same but queried the conspiratorial roles of Africans themselves in what the continent has become in recent times. Godknows Igali in this present work examines the historical problems associated with the African difficulties at state formation, integration and efforts at democratic transition and consolidation.

Historically, the author explored the roles of African nationalist leaders in creating the enabling environment necessary for pursuing national integration at independence. Citing great speeches of great Africans of the pre-independence era, the author highlights the capacity and capability of Africans to do the needful for their respective countries, capturing the thoughts of great Africans such as Tom Mboya of Kenya, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Patrice Lumumba of Congo revealing how passionate Africans were in creating a new era.

The author without alluding to it clearly responded to the ahistorical postulations of the biased British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper who goaded the European public to almost believe his fallacies on Africa.

The Cambridge teacher had declared that Africa had no history; that the history of Africa was nothing but the history of the activities of Europeans in Africa. The author’s robust contribution in this work must be taken to be the much needed intellectual heritage worth bequeathing to the world in utter deflation of the balloon of falsehood popularised by Trevor-Roper.

The author clearly identified three typologies of military coupists to the effect that… ‘Some of them are basically personal dictatorships, some are revolutionary, and others are reformists’ regimes.’

While a preponderant number of analysts have scored military rule low, the author with several years of experience in government rejects a blanket condemnation of military rule. To him ‘their performances have varied from poor performance to some that effected revolutionary changes and others that attempted to advance nation state formation and political integration.’

He, however, identified Mobutu Sese Seko of old Zaire Republic, Jean Bedel Bokasa of Central African Republic and Idi Amin Dada of Uganda as those that made no impact on their respective countries.

Perhaps, the most profound contribution of ‘Perspectives on Nation-State Formation in Contemporary Africa’ is its adoption of a new analytical framework in the study of African history.

The strength of the book lies in the pain staking effort by the author to literally transport Latin America to Africa in the onerous task of finding understanding to African problems that are most similar to those of Latin America.

It was thus appropriate to analyse Africa’s teething problems from the prism of other regions that had passed through similar challenges. The book had a number of suggestions that could address the African predicament but it also gave much vent to external causative factors to the prevailing African challenge.

However, exploring African dilemma from independence to the present would require more analysis to what Africans themselves have done to either lengthen the sufferings of the continent or ameliorate same. The author drove home the point by affirming that ‘diversities are now used by political entrepreneurs as weapons of division and disunity rather than building blocks of integration and unity.’

This affirmation is enough call to any patriot to retrace his steps and promote the interests of the fatherland. This call is most timely at the moment and Africa will certainly be the better for it.

• Prof. Ukaogo is with the Department of History and Diplomatic Studies, Federal University Wukari, Taraba State.